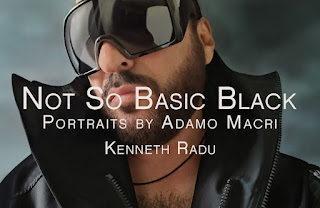

Not So Basic Black: Portraits by Adamo Macri

by Kenneth Radu

Part One

Two black leather-clad bikers on hefty motorcycles slowed down in front of my house this past summer, as if they wanted to stop and speak to me. Only a few metres from the roadside, I was in the midst of deadheading geraniums. Both drivers wore a black helmet with a black visor pulled over their face, so it was impossible to see their eyes or expressions. One could fancy them as alien beings. Surprised, somewhat anxious, I straightened up to prepare myself for a harmless question above the grating noise, or a baleful encounter. The drivers revved their engines, however, and roared off. I only mention this incident because several recent, exquisitely composed portraits by Adamo Macri not only remind me of the bulky bikers, but also leave me astonished and uneasy.

Flanked by Concrete, and Civil Degree, and 29.05.24 present strong, subtle and disturbing images. Although one can sense an underlying element of irony and humour, even to the point of self-mockery, especially in 29.05.24, I also see darker undertones, just as I sensed with the bikers straddling their hogs. My uneasiness is intensified when I study these portraits and their relationship to the eerie, otherworldly headpiece entitled Interloper Ruse, and the macabre Nevermore.

|

| Flanked by Concrete - Civil Degree - 29.05.24 |

|

| Interloper Ruse - Nevermore |

Readers will understand my apprehensiveness when they notice the startling similarity between the head of Interloper with its sand-coloured, bone-like structures rising out of the skull, and the black tuque worn by the figure in Flanked by Concrete, whose right shoulder is so close to the cement-like background that it looks as if the figure is emerging from the concrete itself. Dark shadows on the face in Interloper Ruse threatening to deepen to black, this figure reveals Macri’s fascination with amphibian ambiguities, human origins and archeological structures, as if he is delving into and digging up a mythological or alien past.

|

| Flanked by Concrete |

|

| Interloper Ruse |

There are similar structures elsewhere in Macri’s work, notably the creature in Exuviae, and Jahrfish hazmat. Given Macri’s acute attention to design and detail, and his recurrent motifs, the resemblance is neither coincidental nor arbitrary. The tuque in Flanked is also reminiscent of the head gear worn by the terracotta soldiers of China, further intensifying the idea of something excavated from the past, or retrieved from an alternate universe. Not surprisingly, admirers have also likened the figures in Civil Degree and Flanked by Concrete to soldiers or warriors or some kind of superior individual, social rebel, or someone gifted with supreme self-confidence. That is as may be, but my thoughts don’t quite go in a bellicose direction here, regardless of the head piece and leather jacket.

|

| Exuviae - Jahrfish hazmat |

|

| Civil Degree |

We can’t avoid the eyewear. They absorb a disproportionate amount of space in Adamo Macri’s recent, riveting portrait Civil Degree. The eyewear in all these portraits is so prominent that I keep staring at the oversized, dark pair of sunglasses and think of the black helmet and visor worn by the motorcyclists. Although we may express what we think we see behind the dark eyewear, Macri’s eyes are not visible, so we can’t really determine what his ideas or feelings can possibly be based upon what is hidden. As in many Macri portraits, the lenses reflect, they do not reveal. And that, it seems to me, is central to Macri’s vision, so to speak. When he chooses to reveal his eyes, as he does in Damo 2013, among other works, they rivet attention.

|

| Damo 2013 |

Again, I am reminded that however tempting it is to analyze the portraits as if they are autobiographical or allegorical, the temptation can lead us into highly subjective, romantic speculations, some more convincing than others. Wary of overburdening Macri’s heads with the weight of my thoughts, I prefer to see the portraits as variations of human identity and personality, reflections of multiplicity, gender-shifting, as well as the nature of any individual’s being and desires. True, in a self-portrait the artist may reveal something of himself, but Macri’s portraits are not portraits, strictly speaking, of his own self as much as they are portraits of alternative identities, or ever-changing series of unknowable selves, phenomena that are universally applicable. Moreover, there are many elements of cultural and historical influences in theses portraits which elevate them above the personal, thereby layering them with implications that cannot be fully fathomed. Diane Arbus is astute in her comment about photographs: “a picture is a secret about a secret, the more it tells you the less you know.”

The longer I peruse the portraits, despite their innate secretiveness, the more I become aware of the extraordinarily constructed shapes, the spaces they absorb, the impact of the colours, specifically black, and the meaning all convey. However bold the colour black in Macri’s handling, which supports observations about intimation, power, masculinity, etc., it’s also a study in contradictions and suggestiveness. Black in Western art and literature often carries a history of negative meaning. Large black birds are still associated with the unsavoury and maleficent, ever since Job sent out a raven to discover land. Once it did, the bird settled down to feed off carrion, refusing to return to the ark. And so, in western cultural and personal imagination, black often signifies evil powers, violence, death, grief, offensive masculinist attitudes, bikers included, even sexuality in certain contexts. Of course, art is filled with representations of the dark side, if you will. I think of Goya’s Black Paintings: The Witches Sabbath, or Asmodea, Atropos, or the horrifying Saturn Devouring his Son, or Malevich’s Black Square, to name a few.

|

| Francisco Goya’s Black Paintings |

|

| Black Square |

On a gentler note, there’s Manet’s The Dead Toreador in which the preponderance of black creates a sense of stillness, as if the toreador is resting. Without necessarily implying nefarious activities, black is prominent in some of the art by Frank Stella and Robert Rauschenberg, or in Japanese prints, but I am wandering beyond my ken, so to speak. In Western art, black has the power to unsettle received notions, remove us from our comfort zones, and lead viewers to consider new ways of seeing, if I may allude to John Berger’s documentary series, Ways of Seeing. It creates memorable aesthetic, emotional, and indeed sociopolitical effects, evident in painting, photography, cinematography, and in other forms of art.

|

| The Dead Toreador |

Part Two

How is Macri using black in these captivating portraits? Elsewhere, his emphasis on black is energetic, perhaps satirical; for example, in the portrait 14.02.21. The shape of the oversized glasses in 29.05.24 are like a raven’s wings, a shape modified but repeated in the collar of the jacket in Civil Degree and Flanked by Concrete. The angularity creates both a sense of bravado and intimidation, and in certain images they suggest the beginning of a transformation from human into another creature or identity, as in The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts. The underlying concept of and insistence upon shifting into new forms of being is so integral to Macri’s art that I cannot assume that I know who he is as an individual, or what exactly he is doing in any one portrait. The portraits undermine my certainty, even as they lend themselves to a wide range of interpretations by admirers, who may also project aspects of themselves onto the portraits.

|

| 14.02.21 |

|

| 29.05.24 |

|

| The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts |

The titles of these portraits offer clues to meaning, but they’re also more unstable than definitive. Interlope, as we know, means the intrusion of someone or something where it’s not wanted or doesn’t belong. Ruse implies deception or trickery. Who is being deceived? Who or what has encroached? Flanked seems self-explanatory, but the word has contrary meanings: one is either covered or protected on either side, or one is attacked from either side, depending upon context.

Perhaps Civil Degree is less ambiguous, except one can’t really determine to what the word civil applies. Is the figure in the portrait, having restrained supposed ferocity, now acting in a civil manner to a degree? Is civility a matter of degree anyway, a convenient pose or arbitrary mood rather than an absolute, ethical state of being? Are we to assume the man is essentially uncivilized, potentially savage, and has temporarily cleaned-up for civic purposes? In both Civil Degree and Flanked by Concrete the glasses are rounded, as if the wings have folded inward. The portraits suggest either a pause before action or a rest after it. We cannot know. The titles, therefore, lead us to certain interpretations, but always ensnare us in possible misconceptions because we may miss the irony or satiric intent in the portraits. In Macri’s art, there’s always more than meets the eye.

What’s also strikes me in Civil Degree are the precise edges of the glasses, the jacket, the zipper, the beard, the hair, the string around the neck, even the ears and lips, as if the man has been to a salon for a makeover and emerged laundered and refreshed. Consider the precisely trimmed beard, and not one hair is out of place in Civil Degree. Macri pays particular attention to the hair in all his portraits, as I have written elsewhere (Hirsute Pleasures, Getting in Adamo Macri’s Hair). This carefully manicured surface seemingly contradicts any idea of bellicosity. I use the word surface, for we can only surmise what is hidden or suppressed.

The head in Flanked by Concrete, however, is less clearly defined, especially the right side where the shoulder and wall are almost indistinguishable. The head, of course, is covered with a tuque whose shapes call to mind the Terracotta soldiers of China, as well as the sculptured skull of Interloper Ruse. The jacket is less clearly defined than it is in Civil Degree. The eyes remain hidden behind preponderant glasses. The background does indeed appear to be concrete and one can interpret the portrait accordingly, given the title. Certainly, the covered head seems to have emerged from the background, flanked or protected by, or inseparable from it, depending upon one’s view, as if it is a part of, or growing out of an inanimate matrix. As an artist, Macri is fascinated by the emergence of new, alternate forms of being, not all entirely human.

|

| Terracotta soldiers |

The face is lit as it is in Civil Degree, and more brilliantly so in 29.05.24. In the latter portrait, instead of a leather jacket with all its dubious connotations, the figure wears what looks like a silk tuxedo, and he sports a black flower in the lapel. With two chains around the neck, a man is dressed for an occasion, for a particular kind of soirée. There’s still a heavy reliance upon black, but the flower and glasses whose shapes are similar, undercut any sense of danger or warrior or lone wolf intimidation. The head is quizzically tilted, the right shoulder elevated, as if the figure has been caught in a shrug. Indeed, the portrait possesses an insouciant air, however carefully constructed. Devoid of threat, eroticism and humour enrich this portrait with its touch of self-mockery, reminiscent of the French Decadents at the end of the 19th century, who wore green carnations in their lapels, following Oscar Wilde’s lead.

Contrary to the polished use of black in these portraits, in the work entitled Nevermore neither clarity nor satire is present. To end my own speculations, I compare it with the previous portraits to demonstrate Macri’s masterful handling of the depths and implications of the colour black, as well as illustrating his range of effects and narrative art. In Nevermore, we are in the territory of Goya’s Black Paintings. Macri presents viewers with a portrait of a man in the grip of nightmare, a man who cannot emerge from the black cauldron of despair into any kind of light. Unlike Civil Degree or Flanked by Concrete or 29.05.24, this is not the portrait of a warrior, confident bon vivant, lone wolf, or polished trickster. Nor is it the head of a mythological or alien being. Unclothed, his hair unkempt, the head half-disappearing into a black background, the man is trapped in terror. Of course, the title comes from Poe’s haunting poem, The Raven, and Macri’s portrait illustrates a remarkable reading of it on YouTube.

|

| Nevermore |

And the eyes!! As if gouged out, the eyes are replaced by black vacancy, and I recall the hollowed or blackout eyes of Jahrfish hazmat and Interloper Ruse. Nor are there sharp and precise edges in Nevermore: all is confusion and horror. Hence, the light is diffuse, obscuring rather than clarifying, as if the head itself is slowly disappearing, degree by degree, into the swallowing black where nothing can be seen and there are no eyes to see it. Never more.

Kenneth Radu has published books of fiction, poetry and non-fiction, including The Cost of Living, shortlisted for the Governor General's Award. His collection of stories A Private Performance and his first novel Distant Relations both received the Quebec Writers' Federation Award for best English-language fiction. He is also the author of the novel Flesh and Blood (HarperCollins Canada), Sex in Russia: New & Selected Stories, Earthbound and Net Worth (DC Books Canada).

Not So Basic Black: Portraits by Adamo Macri

Essay by Kenneth Radu - 2024