In My Dark Gallery: Recent Adamo Macri Portraitsby Kenneth Radu

Part One:

It’s common knowledge, or commonly stated, that we cannot really know anyone and that we all wear masks of one kind or another. As an artist, Adamo Macri has made stunning use of masking throughout his oeuvre, paradoxically concealing as much as revealing. I think it’s useful to remember that Macri has explained that, for practical purposes, it’s more convenient to use himself as a model for his extraordinary portraits of shifting and various identities than it is to hire someone else. For that reason, we cannot presume to know who Macri the man is, or what he believes and feels. By using his own face, the artist liberates his time and creativity, and allows us to see a multiplicity of faces, aspects of human character, desires, fantasies, anxieties, fears, despair and rejoicing, often within the context of larger social or political realities. Macri’s subject, therefore, is not himself, but his viewers and society.

Studying several recent portraits by this intriguing artist, Gerasim, Intermezzo, and Street Art, Citing A Medium, and Vice Not Virtue, all dated 2024, I don’t presume to analyze Macri the artist as an individual. I try to understand Macri as the artist of human drama and contradictions in which all viewers participate. Having written so much about his work over the years, I sometimes think that I have done with this artist. What more is there for me to say; I repeat myself; there is nothing new under the sun; I have reached the point of saturation. Startled and thrown over so often by his art, I try to convince myself that I’ve had enough of discombobulation. Time to turn the page, turn the corner, turn back, turn over. Whenever I do feel myself turning in that direction, however, I see another Macri portrait, which once again causes flames to flare up from smouldering embers. I begin to burn and must write through fire and smoke, so to speak. To change metaphor, in one of his letters to a writer friend wherein he offers condolences on the death of her mother, Flaubert suggests that she throw herself into work: Ink is an intoxicating wine: let us dive into dreams since life is so terrible!

Allowing for profound changes in the times and the technology of writing, Flaubert’s comment explains much as to why I, metaphorically drunk, write, albeit on a keyboard. Macri’s art becomes a catalyst for my own endeavours. More to the point, and this goes to the heart of what I see in his brilliant work, he encourages viewers to dive into dreams, explore nightmares, enrich their empathy, understand alternatives and satire, and to laugh at themselves. Above all, Macri reminds us that one function of art, at least, is to render life less terrible, even as it reminds us of how terrible it is, or can be. To return to the image of Macri’s art as arousing fire, I embrace the conflagration.

Despite the prevalent use of masks and the masking effect of dark eyewear in Macri’s art to conceal the eyes and by implication the person, the mask may have other meanings besides disguise or deception, secretiveness or self-effacement. Moreover, although one may speculate about what the man is hiding behind his glasses, I find It more interesting to consider that viewers may see themselves reflected in the lenses. This seeming contradiction whereby the mask is not a covering of the artist so much as it’s an exposure of the viewer is apparent in the electrifying and complex portraits, Intermezzo and Citing A Medium. In addition, I also see a fascinating engagement, both seriously and satirically, with the moral choice between good and bad, or, as the title of one portrait explicitly states, Vice Not Virtue.

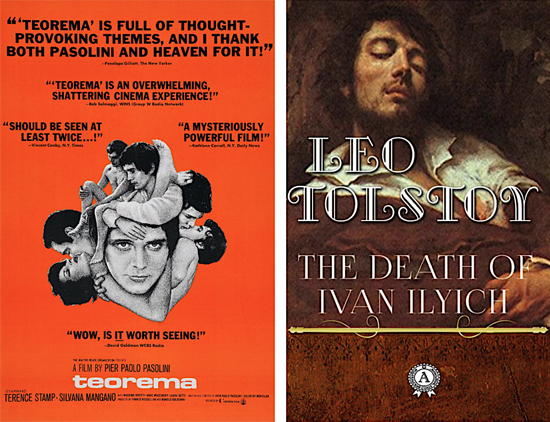

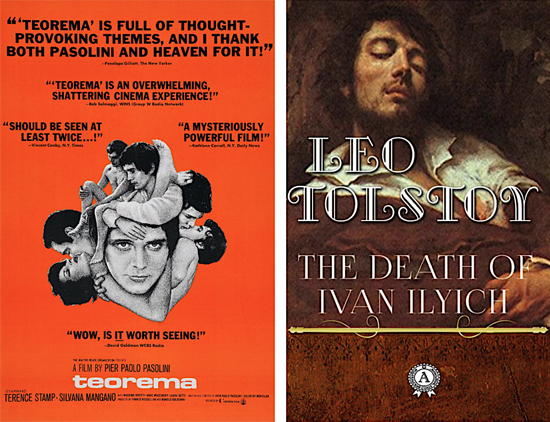

So, I find myself standing in an imaginary gallery, surrounded by Macri portraits. The only light is that which illuminates the individual pieces of art, as well as the subtle manipulation of light in the portraits themselves. Among other things, Macri is a master of lighting effects. Immersed in the very fabric of the portrait itself, I also become more and more aware of his architectural instincts, for want of a better word. Impelled by a vision, Macri builds or makes concrete by designing, arranging patterns, selecting materials, balancing the concrete with the intangible, layering and qualifying, until he has achieved his purpose. So, I take several steps back to gain a better perspective of Gerasim, a portrait which is so deeply resonant that I remain entranced and perplexed by what Macri is attempting here. Perhaps viewers have seen Pasolini’s provocative film Teorema and also read Tolstoy’s profound novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, which inspired the film. As I concentrate on this portrait, remembering elements and characters from the film, as well as Tolstoy’s novella, which I have taught in a college course, a curious event occurs: Gerasim and all the portraits seem to come off the walls and begin circling me, as if I have stepped into the middle of a hologram of whirling faces.

Part Two:

Tolstoy’s Gerasim is a gentle soul, a peasant who devotes himself to caring for the dying Ivan Ilyich, a man whose life has been distorted by materialism and social status. Now terrified by the prospect of an early death from cancer and spiritually in despair, he is appalled by the seeming indifference of the people around him. What had made him so special after all? Why must he suffer so? Why must he, in fact, die? Only from the unsophisticated, utterly unselfish Gerasim and his unquestioning religious beliefs does Ivan acquire a sense of comfort, consolation and spiritual awakening. Pasolini’s film, albeit inspired by Tolstoy’s story, goes in a different direction: a young man, the visitor, played by Terence Stamp, provides emotional and sexual satisfaction to unhappy members of a troubled household. Assuaging their pain and giving sexual satisfaction, he doesn’t ask for anything in turn. Their “salvation,” however, seems to be dependent upon his presence. Once he inexplicably leaves, each member of the family must confront their demons and deal with the consequences of their actions and attitudes, without divine assistance, so to speak.

As Macri’s Gerasim looms towards me, swerves, and turns aside, I see that the artist combines both the spiritual and sexual in his rendition of the saintly saviour. Notice the length of beautiful, earth-brown hair, suggesting peasant origins, as well the bare shoulders and arms wrapped around a pillow, perhaps in bed, not alone, either pre or postcoital, certainly sexually suggestive. And the light! The off-white hue of the walls and pillow, the light skin tones of the upper arms and shoulders, the inexpressive or neutral look of the face with sharply etched lips and nostrils, the shape of the former corresponding with the shape of the latter, the precise cut of the beard: all contribute to an aura of gentleness and erotic compassion. The dark, circular glasses the eyes and obscure individuality, but more powerfully and significantly they highlight the sexual allure of the face, emphasizing simple, nonjudgemental humanity.

Masculine and feminine qualities coexist in this portrait, and it’s not really possible, or desirable, to extricate one from the other. The beard and hair are masculine, but they are so well-coiffed, the skin so smooth, that one can sense a feminine sensibility at work, at least one that is free from the restrictions of gender.

Macri has long been fascinated with gender identities and often undercuts social norms and definitions in order to present alternative sexuality. And, yet, as this portrait looms towards me, recedes then returns, I become aware of a small, out of focus portrait on the wall above the left shoulder. Just a dark note in an otherwise unblemished, sin-free world. One can’t identify it, but the hint of a darker, shadow self in this bright and delicate portrait of human loving is disturbing.

Just as I am disturbed by another portrait, which displaces Gerasim and circles daringly close to, then tantalizingly distant from my eyes. The gallery walls seem to dissolve, and I am caught in the midst of three-dimensional images vibrant with life and implication. Disturbed because it’s both comic and intimidating, a portrait wherein the eyewear immediately draws my attention and raises alarm. No one who sees Vice Not Virtue can fail to respond to the silver, cone-like daggers protruding from the tinted glasses, a comical accoutrement, something a movie star or rap artist might wear just for the sake of drawing attention to himself and being outré. From a satirical point of view (one should always be aware of the degree to which Macri is pulling our legs), the image seems to be playing with viewers, just as the artist plays in the portrait Male Head with Moustache. So, yes, Vice Not Virtue is bursting with bling and it’s fun, but humour aside, in this portrait the glasses intimidate more than they amuse.

A darker and less androgynous portrait than the sexual and spiritual Gerasim, Vice Not Virtue depicts a potentially aggressive character in a momentary pause, as if thinking what his next move will be. The hair is less lustrous and feminine than that of Gerasim. The beard, although trimmed, has a touch of roughness, but that’s the result, I think, of the overall impact of the image. If the purpose of a character like Gerasim, both in Tolstoy’s story and in Pasolini’s film, is to alleviate human frustration and suffering, and help people understand what needs to be done to resolve their conflicts, the title of Macri’s portrait Vice Not Virtue suggests otherwise. I cannot see the eyes, nor can I make sense of the reflection in the lens, which would include that of anyone who dares to peer. Get too close to this face, however, and one risks being pierced by the eyewear.

In my imaginary gallery of holographs, I find myself stepping away from it. Even the silver necklace suggests a live serpent writhing around the neck above a black-clothed torso, ready to strike. Study the exposed ear long enough and it appears more and more pointed, either elf-like or demonic, depending upon one’s notions of vice anthropomorphized. And what does the artist mean by the title, Vice Not Virtue? Is it a matter of mere preference or temporary fashion statement, or is the artist objectively depicting the moral struggle within an individual conscience between good and evil intentions? I cannot say, except the terminology is as religious as it is secular.

Part Three:

There is sometimes a religious underpinning to Macri’s portraits (one sees it in Pinus Attis, for example), if not doctrinal, at least spiritual, and certainly present in Gerasim. When responding to Vice Not Virtue, after viewing Gerasim, my eyes also search among the shifting whirligig of images for the curiously entitled Street Art, a portrait, which for all its contemporary look, reminds me of a heavily cowled Mediaeval monk on his way to vespers. The golden light of the eyewear hides the eyes for the most part, but in this instance the shading indicates a kind of self-effacement, rather than concealment, humility in the face of a larger, arguably divine power. The background colour is reflected in the glasses and the skin tone, as it often the case in a Macri portrait, and here the golden hues intensify both quietness and depth of feeling.

Street art includes chalk on the sidewalk and graffiti on public walls, ranging in quality from mere scrawls to sophisticated images, from the whim of the moment to a considered artistic purpose. The zipper of the black hoodie is undone, causing the cloth to separate into two equal parts and split the Rorschach-like image on the chest in half, an image that resembles paint splatter in keeping with the notion of street art. Except the white image appears designed rather than arbitrary. I wonder what the gothic-looking script on the hood says or signifies. I cannot read it, but that may well be the point. Whereas the physique in Vice Not Virtue fills the black cloth, in Street Art it seems to recede within it, as if disappearing. Once the hoodie is completely zipped up, the body becomes wrapped up in a body bag.

The human being in the cowl is potentially vanishing, black-shrouded in an alternate, or parallel, atmosphere of gold, just as the human elements of Intermezzo and Citing A Medium also seem to be, if not disappearing, at the very least being compromised. Perhaps compromised is the wrong word: altered and blended is what I mean, a reflection of Macri’s fascination with the relationship between human and the nonhuman. The mask in these portraits could be regarded as the actual eyes of beings who have evolved out of contemporary digitalization of reality, the interface between flesh and technology, and the recreation of identity by non-human powers.

It serves little purpose here to speak of the hidden character or psychology of the man, or reasons why one hides behind a mask, because there are no eyes behind these masks. The meaning is exterior, all surface, sharp and shiny like art produced by AI. We see the receding of the human to a degree in Vice Not Virtue, but in Citing A Medium and Intermezzo, Macri plays with and pushes the concept, if not to its logical conclusion, whatever that may be, then certainly to a provocative edge. One reason that his art remains so compelling, aside from the technical mastery abundantly displayed in these fine portraits, is Macri’s acute awareness of shifting concepts or standards of what makes a human being human in the age of virtual realities, artificial intelligence, and manufactured body parts.

Part Four:

And what is less human than the bestial hand in Intermezzo? The gallery space around me darkens; all I can now see are these two astonishing portraits circling my head. They are suffused with so many elements that my mind is a whirligig, dizzy with fragments from past portraits and renewed efforts to grasp and understand. The monstrous hand of Intermezzo, or variations of it, appears in other Macri works, notably Icono Emoter. Notice how it’s poised, raised and ostensibly resting on the breast, like a hand in classic portraits. It’s remarkable that the eyes are not hidden, but boldly exposed and surrounded by a silver-coined mask which, however operatic, is disquieting. Its purpose is to draw attention to the eyes staring at the viewer, not to conceal them.

The circles are reflected in the necklace, the pendant, the epaulets. The mottled black clothing appears textured like fur, also present around the wrist of the hand, and is reflected in the background, thereby emphasizing both the theatrical and bestial aspects of the portrait. Dare I say that the claw-like hand is the left. We all know that the devil in folklore is left-handed. The word for left in Latin is sinister. Enough said. The long dark hair is loose. The face is inexpressive, as in most of Macri’s portraits, because expression is interpretation and he takes great pains to avoid it.

The word Intermezzo, for all its musical and theatrical connotations of a pause between events, a musical entr’acte between major sections of an opera, also means an individual piece performed by a soloist within a larger musical context, say a lengthy Mahler symphony. In the context of Macri’s portrait, it does indeed suggest not only a single and singular performance, but also one that is not ultimately isolated from what came before and what comes after. The word intermezzo, therefore, can be interpreted as the pause, the moment of reflection, that comes after we think we know who we are or what we want, like the characters in Tolstoy’s story and Pasolini’s film, and before the unknown, inescapable waiting to be revealed to us in the second half of our acted lives, so to speak.

Macri is extremely adept in his use of black throughout his oeuvre, something I have considered in a previous piece (

Not So Basic Black), and his skill is equally evident here. In fact, the work reminds me of various arrangements of black in James Whistler’s paintings. I try to step aside the portrait as it looms before me, but hesitate, because the longer I pause the more I see. It’s to Macri’s credit that he creates portraits that repay attention, that demand attention, and leave their imprint on the imagination.

So, I study the hand in greater detail: the long hand of a musician, devil or not, and I recall the old film Intermezzo, starring Ingrid Bergman and Leslie Howard, both of whom play musicians, the former a pianist, the latter a violinist. Their love affair leads to potential tragedy. The experienced, wrinkled hand with its gift or skill is what brings the lovers together, but passion in the ordinary world can be destructive. Macri’s hand, whether it’s in a special glove or not, is anything but ordinary. If the artist is blending animal and human, implying the conflict between passion and morality in Intermezzo, a pause between the beginning and the ending of transformation, he is equally adept at creating a creature that is part human, part technological, an android so to speak.

Despite its loveliness, Citing A Medium disturbs me as much as any of the other portraits. It’s very stillness, wrapped in hues of brown, gold and black, with a touch of silver, suggests waiting and inactivity, as if needing to be plugged in like an electrical vehicle charged to make a move. This sense of human become android is heightened by the Robocop eyewear, another image from the movies, which is not surprising given Macri’s fascination with the imagery and structure of cinema. For that reason, the title intrigues me. Is the portrait “citing” an image from another medium? We have to remember that Macri is a multimedia artist whose work involves photography, painting, sculpture, technology, biology and detritus. Or, do I, as a viewer who is trying to make sense of what he sees, “cite” an image from the works to defend my own point of view. Or, is the title a satirical jab at scholarship: don’t write anything unless you can “cite” the source.

The figure seems to emerge from a matrix of brown, the earth so dearly beloved by Gerasim the peasant, and is lightened by a remarkable silver necklace, a jewel devoid of traditional gems like diamonds and pearls, emeralds and rubies. It hangs down like a strand of the dark hair. On either arm of the jacket is a square patch, difficult to see, but connected with the notion of the unknown, worn by a character with the piercing, digital vision beyond that of human eyes.

Somewhat overwhelmed by the circling three-dimensional portraits swirling about my head, I have gone on too long, allowing myself to get lost in a labyrinth of speculations. Then, I remember that Daedalus designed the labyrinth to contain the monstrous Minotaur, an architect of a wondrously complicated structure, like Macri the architectural artist whose art may twist and turn, leading in several directions either towards a metaphorical monster silent in darkness or the angel awash in light: vice or virtue. Intoxicated by the act of writing, wearied, and maybe writing for the last time, I also feel reinvigorated and enriched by my enduring, relentless fascination, perhaps obsession, with Macri’s portraits. They float in the dark gallery of my imagination, intangible structures weighted with meaning, inviting viewers into their frames, offering visions of alternative beings and implications in a dark and terrible world, letting us all, to quote Flaubert, dive into dreams.

In My Dark Gallery: Recent Adamo Macri Portraits