by Kenneth Radu

Part One

While admiring Adamo Macri’s intriguing portrait, Aerosol, I remembered holding a candle and walking with my mother before midnight outside the Orthodox church of my childhood, a symbolic ritual in celebration of the risen Christ on Easter. Even though it’s been decades since I’ve participated in the religion of my birth, remnants of it lurk or linger in my mind, just as religion often crashes into daily news, never more so than in a so-called secular society. Macri’s Aerosol, so beautifully coloured in purple tones, depicts either the intimate connections and/or divisive tensions among organized religions, in this instance primarily Christianity and Islam, and their co-existence within society. Given the element of play and provocation in many of his portraits, the artist may well be, to quote Hamlet, playing the part of a “satirical rogue.” Leaving aside the title for a moment, consider the clothing in this portrait with its unavoidable cultural and religious significance.

|

| Aerosol |

I don’t think any artist chooses clothes or colours more carefully for portraits than Adamo Macri. He pays as much attention to the texture, folds, patterns and reflections of cloth as, say, James Tissot does in L’Ambitieuse, a skill demonstrated in the “colourful” and satirical portrait Coded Palette, or in other works like Street Art, Intermezzo, and Fiefdom Edict, to name a few. In Coded Palette, the “Jesus” hoodie and the shock of brilliant green hair especially command attention. The combined effect of outlandish hair and hoodie, the dots of colour on the face which suggest a painter’s palette and introduce an element of clownishness, as well as the oversized eyewear, all lead me to imagine a blending of Lady Gaga, punk rocker with a touch of David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona thrown into the mixture.

|

| L’Ambitieuse (James Tissot) |

|

| Coded Palette |

|

| Street Art - Intermezzo - Fiefdom Edict |

So taken aback by the daring imagery and composition of Aerosol, remembering my childhood experience of walking around the church, waiting for Jesus, I wondered about the preponderance of religious imagery in this work. In some of Macri’s portraits, there are overt or subtle religious elements, explicit or implied belief, but never dogmatic or doctrinal. One need only study such creations as Gerasim, Pinus Attis, and Memento Mori, among others, to see evidence of Macri’s sensitivity to the hidden and intangible, whether in heaven or in hell, under rocks or in ocean caves, within cellular structures or folds in the brain. It also indicates his artistic awareness of the complex and contradictory attitudes to identity, gender, sexuality, and the tensions between flesh and spirit on the unsteady grounds of everyday life.

|

| Gerasim - Pinus Attis - Memento Mori |

Of the striking elements in Aerosol, none is more so than the figures of Jesus on the robe. His head and arms raised as if praying to Heaven on the left, in opposition and apposition to the crucifix on the right side. My candle-lit procession outside the church celebrated the resurrection of Christ: an event reflected in the words that family members used on Easter morning. Holding my blood-red egg, I tried to crack a similar egg in my brother’s or sister’s hand, saying, "Hristos a înviat!" (Christ has risen!), and they would respond "Adevărat a înviat!" (Indeed, He has risen!). One has to eat the egg afterwards, of course. I preferred chocolate eggs with cream inside. Macri’s portrait, however, raises the question: is Aerosol devotional or satirical? And I am reminded that humour, however dark, like religion and sex, can be a response to death and the absurdities of various religious practices.

Upon a close inspection of this portrait, I see significant alterations in the body of Christ; for example, the head of the Christ figure on the cross. It virtually disappears in a dark smudge or cloud, reminiscent of the head in Nevermore. The elongated arms look like bars, the hands disappearing, no sign of nails through the palms.

|

| Nevermore |

There have always been laws in various societies regarding the consumption of goods and/or the wearing of apparel, prescribing what members of a certain class can wear and others cannot, including colours and fabrics. Yellow, as we all know, was exclusively reserved for the imperial family in China, forbidden to ordinary citizens. Clothing can be a political statement as much as a religious one. Macri’s portrait particularly resonates in contemporary Quebec, and therefore may also be implicitly political, given Quebec’s Bill 21, “a law that bans those wearing religious symbols, a cross, a kippah, a hijab or turban, from holding public sector employment such as a schoolteacher, a prosecutor, or a police officer.”

Apparel oft proclaims the man, Polonius’s advice to his son Laertes, which is to say, avoid sartorial exhibitionism, or clothes worn for the sake of appearance that threaten to trivialize one’s character. In Macri’s Aerosol, the figure, who isn’t by any means trivialized, is perhaps female, or perhaps androgynous, or perhaps cis-gender, but I don’t think gender is the issue here. When Macri wishes to produce gender specific portraits, he does, as a perusal of his oeuvre demonstrates. In Aerosol, however, gender seems to disappears entirely behind a welter of significant attire. Here, religiously associated garb is on display with a vengeance, as it were: not only a hijab and niqab in shimmering purple, but also the Jesus imprinted robe and a tight-fitting head covering, call it a bandana, under the hijab. Unlike many Macri’s portraits, the eyes are not covered. I suppose the temptation, therefore, is to read into the eyes and imagine what the figure is feeling or thinking, but in truth I, like most viewers, project my own thoughts into the character. It is all speculation, perhaps interesting, sometimes apt, sometimes wrongheaded, always subjective. The glittery eyeshadow, however, is the only sign of human individuality, applied in defiance of oppressive laws.

The title Aerosol is a curious choice for such a religiously loaded image. Is it a code, a word which harkens back to Coded Palette, indicating a meaning, not immediately apprehended but embedded in the imagery and its associations, one that has to be worked out? I don’t believe Macri is playing arbitrary games with viewers or deliberately trying to trick them. He is, though, profoundly alert to depths and labyrinthine structures that can derail or alter apparent meaning.

|

| Aerosol - Coded Palette |

A volcanic eruption is a form of aerosol as is a can of whipped cream: a kind delivery system for perfumes, disinfectants, deodorants, insecticides, smoke, etc. Aerosol is both inherent in nature, and created by human agency, for good or ill. The prominent ribs of Jesus in this picture are more sepulchral than living, their lines recreated in patterns in the cloth, and the white, lifeless eyes on the left contrast vividly with the vibrant eyes of the human figure wrapped in silky cloth. The crucified Christ seems to have a key hole in its stomach, which arouses curiosity. Ironically, the Christ figures appear more dead than alive. Apparel in this portrait is charged with meaning and implications. Who, after all, is wearing cerements? In its commingling of religious images, Macri’s Aerosol raises provocative questions, but refuses to answer them, for he’s an artist first and foremost, and not a propagandist in the common meaning of the word, bearing in mind Orwell’s famous dictum: all art is propaganda; on the other hand, not all propaganda is art.

Part Two

It’s also worthwhile to remind ourselves of the role that plastic arts play in Macri’s portraits, that he is as much a sculptor as he is a photographer. Often the heads in his portraits look as if they have been sculpted and rendered supple by colour, lighting and textures, or constructed by an assemblage of artefacts and parts from disparate sources. I think of a recent and amusing work, Male Head with Bugle. Various items surround the face: an artificial-looking, theatrical white beard and a robotic-like hat with strap; crystals in a Fibonacci spiral serving as a symbolic bugle; and other metallic accoutrements. This is not an image of a person so much as it is an idea of a new kind of being, an android, a glitzy metaphor, even an inter-galactic messenger, announcing a spiritual or religious message to mere earthlings, its eyes hidden by a shield like the kind robocops wear.

|

| Male Head with Bugle |

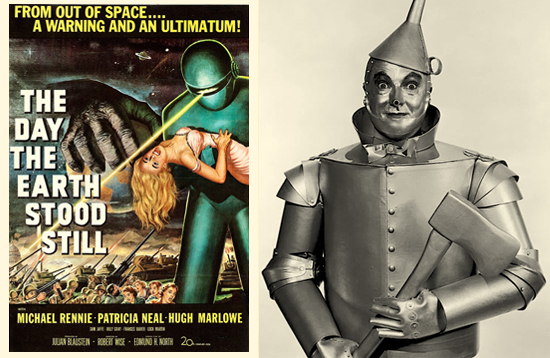

Macri is often influenced by film, even if it’s not the science fiction movie The Day the Earth Stood Still, starring Michael Rennie and a human shaped robot whose eyes, if eyes it has, are covered with a visor. When the visor opens, the creature can shoot destructive rays at a target. Viewers may also think of the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz.

The angle of the head and the weave of the tuque in Macri’s Male Head with Toque, reminds me of the splendid sculpture of the head of an Oba, a Nigerian King, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The title of this work is self-explanatory, indicating simply what is being presented and, yet, like the hats of one kind or another in Rembrandt’s self-portraits, the headpiece in Male Head with Toque is an integral part of the portrait’s depth and meaning.

|

| Male Head with Toque |

|

| Head of an Oba |

A companion piece to Male Head with Toque is Psionic Foresight, displaying the same tuque in a different position, with the hair hanging in a pony tail over the right shoulder. The man wears a dark cloth draped over his left shoulder, the same colour as the hair. Indeed, there’s a preponderance of black, grey and browns in this striking portrait, which deepen, if you will, the allure of the image. Why that is, I don’t know, but feel it is so, except that I do think the man is more connected with the earth than with the sky. One eye, the right, is visible, looking downward, out of a corner behind the reflection in the glasses, certainly avoiding direct contact. We may say all sorts of things about what the figure is imagining or what he actually knows. Macri portraits, after all, can be narratives, which encourage various interpretations, both plausible and absurd, my own included, which is as it should be. Of course, the title of the piece leads us to think about telepathy, or secret knowledge and private prognostications. From there, the imagination can create a story about a shaman or seer or prophet, even attempting to enter into the mind of the subject himself.

|

| Psionic Foresight |

My thoughts, however, do not in that direction tend. This may have something to do with the chiseled look of the face and the rigorously trimmed beard, precisely cut. Psionic Foresight is a tricky title, ironic perhaps, playful, with a touch of deliberate bravado, daring the viewers to imagine what the head in the portrait actually sees or thinks, as if it can predict what the future holds for us. The eye, as mentioned, doesn’t stare at the viewer nor penetrate the viewer’s mind. It avoids the viewer’s gaze, so no one can really see, although one may pretend to see, as we so often do, what emotion, other than wariness and hesitation, the eye possibly expresses behind the lens, crowded as it is with reflections of the outside world. In a sense, the outside is absorbed within and reflected back. But is that special insight, foresight, hindsight, or simply the physiology of seeing through a lens, or through a glass darkly? The latter metaphor brings us right back to religious implications and essential uncertainty of self, as implied in I Corinthians.

The extremely calm allure of the portrait, weighted by tuque, drapery and even the ponytail, invites a long, lingering look, enticed by the suggestive title to fancy possibilities, perhaps, of what is not really there. The head is securely poised in its private thoughts, fresh and precise in appearance. Given the sharp outlines of jaw, beard, eyewear, the loose hair and drapery act as visual counterpoints or contrasts, a freeing from self-imposed constrictions or the burden of knowledge, if one wants to pursue the implications of the title. As for the wonderfully woven tuque, even though it shapes the head like an Oba, it is also the head gear of cold weather, and given the earthy palette of the portrait, I can’t help but think of animals and the coureurs des bois of old Quebec, in this case one who has been spruced up.

I also think of an equally engaging portrait with the punning title, Citing A Medium, words that seemingly sends a direct message to the viewer. Who or what does the man in the portrait see, or who or what do viewers, see, as in sighting? In addition, who or what is the man in the portrait quoting or naming, or who or what do viewers repeat or say, as in citing? Medium is a word equally charged with multiple meanings: a person who is a conduit for spirits or voices from the other side, as it were; a means through which we convey information or create something new; a balance between two extremes or a middle position. In the psionic world, the medium supposedly transmits messages from the other side to those longing to hear them. The portrait is situated between the viewer and speculations of what lies behind it, or, if you will, its provenance.

|

| Citing A Medium |

In Citing A Medium, the preponderance of earthy tones creates a stillness, a poise or pause in the midst of meditation. The eyewear again is more shield than glasses. The emphasis on vertical lines in the hair, the contrasting silver necklace, the reflection in the lens, the open cloth, the barely perceptible ear, all contribute both to a paradoxical sense of other worldliness and dark earthiness. Is the man receiving a message from the other side, or looking into the depths of what is here on earth? Is he in fact endowed with extrasensory perception? Or taking advantage of common fears and anxieties?

We cannot really know what he is thinking, nor can the figures in these portraits know what we think. Despite, or because of, their tricky telepathic and telegraphic titles, the portraits are marvellously constructed concatenations of narrative and visual elements that always lead us to a state of wonder. And Macri’s portraits are indeed wonders to behold.

Kenneth Radu has published books of fiction, nonfiction and poetry. His work has been nominated for a Governor General’s award and twice received the Quebec Writers’ Federation prize for best English-language fiction. He also has written extensively for the online cultural magazine, Salon .II. He has recently completed the manuscript of a new novel, which is now undergoing revisions.

Tricky Titles: Adamo Macri Portraits

Essay by Kenneth Radu - 2025