Restless, unfocussed, strange inchoate stirrings, I rise from my desk and stare out the window. Partially illuminated, the gibbous moon filters its reflected light through the still leafy trees. A walk outside in the autumn chill would clarify my thoughts and relieve tensions, but my computer screen beckons. There is necessary writing to be done. Recent Adamo Macri portraits have seized my imagination and unsettled me. Everywhere I turn, day and night, I carry the images in my head and, yes, in my heart. When I stare long at them, I feel as if I am dissolving in sensations of deliquescence, simultaneously absorbing and liquefying.

Knowing and not knowing, I lose my sense of place and identity. Defined and confined by social conventions in my ordinary life, I shake free of them and become whatever the portraits promise that I might be. As if in the grip of astral projection, a part of myself leaves the body and slips into the Macri pictures like a ghostly visitor. Drawn by their seductive allure and power, I find a vantage point in the wings of the invisible stage to view the artist’s performance: a phantom in the pictures. Each picture is indeed a self-contained drama. I am transported in every sense of the word. I hear the humming of household machinery so I know I have not entirely disappeared. I can name all objects surrounding me, the computer, the desk, the bamboo mat under my chair, but I feel as if I have vacated actual space and entered a spectral realm. A form of madness, some might say: if so, I am mad. I claim, however, that it’s the madness of art, a state of mind having little to do with clinical definitions or symptoms, and everything to do with the ever-changing brilliance of Macri’s creations.

To make sense of what I have seen and felt, I must write a confession of sorts, a personal exploration behind the scenes. My relationship with these particular Macri portraits is in some respects that of an audience to the stage, whether traditional or experimental theatre, but always participatory. One part of me is studying them on the monitor framed by the darkness of the autumn night, even as a mysterious, projected part of me vanishes into the pictures for a private theatrical performance. Almost shaped like sculptures, they are constructed by a perfect blend of acting and art, painting and photography, all imbued with cultural and mythological allusions. Motionless yet dramatic, richly embroidered with detail, silent yet speaking volumes of emotional and cultural depths, the portraits are pieces taken out of larger narratives and momentarily rendered into tableaux vivants. The word construction is apt, for Macri is an artist who builds or sculpts his self-portraits the way a scenic designer builds a set for a play.

Looking from outside the monitor and from within, I feel, think, and go in the directions the portraits seem to lead, although I create the way I wish to wander. The images provide me with materials of suggestiveness and symbolic possibilities. I can go astray and get lost in the brambles and thickets of my own fancies or interpretations, never more so than in the middle of night awash with longings, when reason and logic succumb to the pressures of my desires and fantasies. Macri’s art, therefore, is not an exercise in dogma or pedagogy. However much he occupies center stage, the artist doesn’t tell the viewers what to think like Socrates pointing his finger in the famous painting of the philosopher’s death by Jean Jacques David.

The titles of some of Macri’s pictures, though, do in fact point to a meaning or purpose like the eerie and luminous portrait, Mercury of Golden Fleece, which seemingly ---- seemingly is an important qualification here --- gives away the plot. Other pictures have a nebulous title like the tensely lit Ellipsis, or puzzling Icono Emoter. Even if named Self-portrait, the titles are prescriptive, not written in stone, because the artist doesn’t photograph his “self” in the sense most of us understand by the term self-portrait. Besides, my own self divided in two under the influence of the art, the concept of self is so heavily riddled with psychological and philosophical problems and queries that Macri may well be playing a joke on his viewers. Although he respects us too much to laugh at us, he does expect us to be wary of our presumptions.

Let this personal drama begin with the first picture that leads to my dissolution in the night, the time when I most often travel through, or project myself into the “macricosm.” Composing myself as best I can, albeit emotionally shaken and intellectually riveted, despite the dispersal of my wit in the wings of Macri’s performance, I ponder as music plays. Explicitly named Ţepeş, it is very cool and sculptural in presentation, the head and upper torso carefully costumed and posed in a subdued yet glowing light, the eyes dark and the face expressionless as in many of Macri’s portraits. The title brings to mind a plethora of stories and folklore, movies and popular misconceptions. Who hasn’t heard of Vlad Ţepeş, more commonly confused with Dracula? Fewer seem acquainted with his brother, Radu cel Frumos (the Handsome) who found favour with the Turkish Sultan Mehmet II against whom Vlad waged war and became the saviour of Wallachia.

Not so long ago on a tour of Romania, after consuming a plate of sarmale (cabbage rolls) and sour cream for lunch at a local inn, I slipped on a cobble stone street one rainy afternoon in the gorgeous and ancient town of Sighisoara, reputedly the birthplace of Vlad. I fell, rising unhurt, dignity bruised and wet, in front of the stone façade of the house where the notorious impaler was supposedly born. A plaque on the wall attests as much, and nearby a sculpture of the famous Voivode of Wallachia stands on a rugged pillar overlooked by a church spire. Folklore and mythology colour all our views of this historic medieval town and the surrounding Carpathian Mountains with their veils of mist veils, and haunted forests add much to the storied atmosphere. Although he never set foot in Bran Castle, Vlad is still associated with the edifice, and its forbidding entrance was in fact used in a Dracula movie. Our notions of Vlad are so entangled with Bram Stoker’s novel and inextricable from popular narratives and films of vampires that, regardless of historical doubts and/or facts, people cling to their favourite stories. The truth that Bran Castle was Queen Marie of Romania’s favourite summer residence and love nest interests me as much as its fictional connections with Vlad the Impaler.

Macri is well aware of the historical and cultural baggage that comes with any picture of Vlad, including this remarkable image. Deliberately he has arraigned the head in paraphernalia reminiscent of Vlad’s royal cap with its band of pearls and golden star with a large gem in the centre. Instead of a beard, Macri covers his jaw with what looks like an ornate steel device designed to represent facial hair, a blending of the human and the metallic. One of Macri’s most theatrical portraits, the artist relies upon the cultural drama of Vlad and Dracula to stimulate memories and ideas in his viewers, even if people see other legendary or historical characters.

|

| Ţepeş |

The pose is serene, the expression severe. The smoothness of his skin to which he may have applied stage-makeup to create a sculptural effect, and the subtle interplay between shadow and light, all contribute to an austere and bedecked portrait embedded with restrained, subterranean and possibly demonic passions. Either I am reading into the scene, a man contending with personal demons, or projecting my cultural fancies into the picture, or Macri is indeed performing the role of a stylized Vlad Ţepeş on the center stage of legendary history. Portraying the tension between the demonic and divine, the heroic warrior and the pathological prince, the historical and the legendary, the portrait blazons in my darkened room and attracts by its strange light and content, the content influenced by my own compulsions.

Despite Vlad’s unsavoury practices from time to time, I don’t think of impalement and other tortures, but of a theatrical visage designed to disguise or hide the private person: the individual human being rendered into a public sculpture of regal dignity. Awe conflicting with trepidation, from the stage wings my disassembled and ghostly self observes Macri build up this particular tableau vivant. I remember that Vlad’s father was inducted into the Order of the Dragon, composed of men dedicated to fighting the Ottoman Empire and saving Europe for Christianity. Drac is a Romanian word for dragon (later associated with the Devil), and dracul(a) means the son of the dragon. And we are all aware of the role of dragons in western mythologies. Behind the surface light burn fierce fires of the dark.

Three other pictures have such a discombobulating effect on me that I almost fear disappearing. Regardless of the stages of my dissolution, I nonetheless collect some of my wits, and coalesce my thoughts. Well past midnight, the pictures induce apprehension and complex pleasure, but surely I am safe in the presence of art, without fear for my life dissolving even as I admire. I try to avoid the conclusion after which I am reaching like an exhausted swimmer grasping a floating log in a turbulent sea. I cannot escape the engulfing sea. The inescapable fact of death is implicit in all these haunting portraits. It is to Macri’s great credit that he incorporates ideas of mortality and our human frailty by the use of cosmetics and props, the results reminding me of Hamlet’s words as he holds up Yorick’s skull in the graveyard: Now get you to my lady's chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favour she must come; make her laugh at that.

I switch back and forth among the portraits Ellipsis, Backstage Evidence, and Anther. None of these pictures is morbid or sensational. They are human and marmoreal at the same time, enticing and forbidding, hot and cold, but their cumulative, emotional effects on me are manipulated not only by Macri’s particular genius with lighting and impassivity of expression, but are also created by his emphatically pronounced stage makeup. The more heavily it is applied the more acknowledgment of the fleeting life and decay I see. The face of the artist consists of layers of images, a face multiplied by ideas any viewer brings to it: comfortable, familiar, comic, absurd, spiritual or sexual, or whatever applies, as if my desires constitute a unique palette. Colour is everything here, colour carries meaning: greyish white in Anther; the rose of feverish flush spread like a mask over the nose and cheeks, eyelids and lower forehead; the lower half of his face unshaven in Backstage Evidence, as it is in Anther, and to a lesser extent Ellipsis; and finally the black mascara and emphatic beauty mark of Ellipsis.

|

| Backstage Evidence |

As the title of Backstage Evidence so pointedly states, all three pictures are part of a theatrical process of preparing a face for a drama, whether public or private, whether the quiet spectacle of my feelings and repressions, or the hidden personal drama of the artist. I also ask: evidence of what specifically? The answers are as many as the viewers, for the picture contains the content I put into it, evidence of my own acts and intentions. The picture is obviously more than its title, as Anther so amply demonstrates. Quite aside from its evident botanical import (Macri is fascinated with organic decay and the cellular dynamic of life about which I have written elsewhere), Anther reminds me of a performer emerging out of his dressing room cocoon, wearied and burdened by a private history at which I can only guess. Given the body-fitting white top and petal or wing-like appurtenances, I can also imagine an exhausted angel, or a ballet dancer rising out of white petals to take a first step on stage. Perhaps he is an 18th century French aristocrat exiting a boudoir of white silks and satins and getting ready to promenade down the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. Or he is arising from layers of constraints like a thrust of burgeoning life.

That beauty mark so prominently displayed on the face of Ellipsis is a touch of pure genius on Macri’s part, an artist fully aware of the significance of details. The title means information has been left out, something is missing, something has been removed, something present but not revealed, a kind of self-imposed constraint. As he frees himself from costume, the implied removal of a wig and all its aristocratic pretensions, my imaginary Marquis presents himself in a moment of authentic reflection. The title encourages me to fill in the blanks according to my view of the performance, according to my sensibility and knowledge, and even according to a kind of latter day Romantic yearning I read in the poetry of Keats. It is a moonlit night, after all.

|

| Ellipsis |

For an artist who takes care not to direct interpretation through facial expression, this picture is deeply emotional in the way the Vlad portrait is not. Mascara heightens the melancholy of the man’s condition and social rank. The face unmasked or unrobed in the dressing room, the cosmetics strike me as an attempt to disguise the inexorable and merciless onslaught of time. Yes, I am gazing upon the torn and worn inner life of an actor from the wings, but I also imagine that I am sitting in a cell with a French aristocrat on the morning of his execution before the tumbril enters the prison courtyard. Both present in the picture and outside of it, for I can almost feel my self dividing, I stare through the window at partial illumination of the gibbous moon, trying to resist and yet taken in by a chilling idea, by a heart-rending inevitability of approaching death. Alas, I am old, but desire doesn’t necessarily wither on the gnarled tree.

And yet, and yet, my thoughts breaking free from restraints of mortality and social conventions, I create another scene of Ellipsis. Into a secret chamber of a chateau I go, or enter the cell of a dungeon, hinted at in the backdrop, as if invited by a reincarnation of the Marquis de Sade whose proclivities are infamous and who offers…just what I dare not say, but my imaginings are explosive and terrifying. There’s a cynical hauteur about the face of Ellipsis, a hint of the depletion following debauchery, or a weary acknowledgement of my hesitations, possibly repressions, and the stultification of prohibitive morality with its terror of the perversities and powers of eros. Surely, I cannot be alone in sensing a savage if quiescent sensuality about the lips and dark dark downcast eyes. What words of enticement escape those lips? What tongue? Nor can we ignore the great hidden fact: the body must be naked because we desire it to be so. Macri’s art infiltrates our fantasies, which enact their own dramas on the stages of his creations. The artist wonderfully and painfully sees through our erotic imagination.

Chronology itself is irrelevant in Macri’s world. Regardless of the individual good looks or apparent youthfulness of the artist, regardless of whatever specific age we apply to an individual piece, Macri’s self-portraits are not dependent upon youth like advertisements and movies, nor do they particularly focus on aging. I would argue that one of the liberating features of Macri’s art is agelessness, not in the sense of art for all the ages, although it may ultimately be that, but in the sense that his pictures transcend mere biological chronology of an individual. Forgive me, but enamoured of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, a woman of contrary and multiple faces like Macri himself, I believe Enorbarbus’ famous description is here apt. With just a tweaking or two, it expresses my feelings about Macri’s art.

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety; other women cloy

The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry

Where most she satisfies

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety; other women cloy

The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry

Where most she satisfies

Second Night:

Alerted to alternatives, I sit and breathe in the dark, the only light in the room offered by the monitor and the backlight of the keyboard. My self separated from my self, hear my heart echoing in my head, and I wonder. What is occurring on this imaginary stage? What is the artist as actor really enacting? Perhaps I resort to a dry intellectualism, seek refuge in theorizing, because I fear the inexpressible or forbidden, fear what I should not feel according to externally sanctioned principles, moral authority, and paralyzing code of beliefs? I decide to retire for the night, at least that part of me that can still act.

Next morning I awaken, discomfited by confusing and turbulent dreams of which I recall only snippets, the detritus of the previous day’s desires and events. They include details from the Macri portraits magnified and tumbled about my unconscious life with bits and pieces of experience and history. And faces floated through the dreams, faces attached to bodies, both clothed and naked, lit up from within like dissipated angels cast out of heaven for rebellious and profane desires, or phosphorescent spirits damned for any number of sins until they, too, vanished with every toss and turn. Before breakfast I examine Macri’s images again. I begin putting together ideas of one sort or another, not worrying about their validity, because the ideas arise out of my body – the phenomenon of the body—so invisible in the portraits but always implied – my own body jolted, impaled by the Macri gaze directed everywhere except at my heart and my soft, dissolving flesh.

I wait, filling the day with distractions and duties, desultory reading and writing, until the evening comes, the temperature falls, and the moon begins its silent, white-faced rise in the darkening sky. I remember Georges Bataille and discover that he helps me to understand what I have been trying to say about my responses to the troubling and contradictory meanings of these superb portraits: The whole business of eroticism is to strike to the inmost core of the living being, so that the heart stands still. The transition from the normal state to that of erotic desire presupposes a partial dissolution of the person as he exists in the realm of discontinuity. Dissolution — this expression corresponds with dissolute life, the familiar phrase linked with erotic activity (Death and Sensuality).

|

| Anther |

Yes, stricken to the core, if I may be allowed to exaggerate. Sex and death. I tend to shiver if I allow myself to stay too long with Ellipsis and Backstage Evidence and Anther, portraits glowing in the dark on the monitor, not afraid for my sanity, but aware of the erotic instincts, the very stuff of life, and intensely aware of my own mortality. Death, the antithesis of sex. I am enthralled by these images, admiring the facility of the artist to convey several personages, layering his true self, whatever that may be, with many identities, and in the process, uncovering my own multiplicity and paradoxes. The eyes avert and engage: they appear to not look in the same direction in any of the portraits, nor do they look directly at me, a common feature in a Macri portrait, but that may be illusory or a visual trick. But the black eyes, devoid of light, forever shifting, nonetheless compel me to stare, to succumb to the allure, as if the gaze of the portrait has uncovered my secret self, entering me profoundly like sexual penetration.

I come to grips with the contrariness of being ignored by the actor on stage who is very much aware of my presence in the wings. Attracted by his seeming indifference to my adoration, I cannot resort to religious or philosophical sureties in the face of the inevitable, nor can I expound theories about the relationship between Eros and Thanatos, except for that of our friend Georges Bataille. “What does physical eroticism signify if not a violation of the very being of its practitioners? — a violation bordering on death, bordering on murder (Death and Sensuality). If Cleopatra had “such celerity in dying,” a metaphoric way of saying she rushed to orgasm, we remember that her great and violent passions also led to her death, with some help from Roman conquerors admittedly, but we also know that without her Antony, nothing is left remarkable/Beneath the visiting moon. Well, the moon is passing and the night deepens and I have hungered, need feeding, and like Cleopatra must abide/In this dull world. I don’t budge, and continue to stare from my two perspectives, and work my way through what I am feeling as I live on this private stage with the artist.

Despite the title of Mercury of Golden Fleece, with its echoes of mythological heroism and tactile beauty, I am amazed and perplexed by this image, which arouses contradictory emotions from the combination of elements from more than one myth; something the artist is prone to do. The face beautifully sculpted and lighted, the make-up adroitly applied, the half-shaven head and the hair hanging over the right eye, and the accoutrement of the fleece over the shoulder, the portrait is astonishing. The title derives from the story of Jason and his Argonauts on the dangerous quest for the Golden Fleece guarded by a never-sleeping dragon. There is that dragon again. The highlighted lips and the dramatically coloured cheekbones, and again the compelling use of mascara don’t lead me to think of adventure, dangerous endeavour and ensuing success, so much as they do of depletion and eerie otherworldliness. Moreover Mercury, a tricky and unstable substance, is also a god who among other duties leads the souls of the dead to the underworld.

|

| Mercury of Golden Fleece |

The ghastly pallor reminds me of a creature emerging from a place I don’t care to go, say, Hades, and yet I find him fascinating and vaguely sexual, reminiscent of David Bowie, certainly androgynously erotic, inviting me to join him in the throes of dying and ecstasy. To be fucked into felicitous finality. The half shaven hair, and the blackish-purple lips, the cadaverous undertones of the portrait and the stillness of the face, the strangely highlighted eyes looking at and ignoring the viewer, the cheekbones, the tones of the flesh, desire and repulsion mingled, speak both of loss and lust. The Golden Fleece over the shoulder is ambiguous, for material wealth is neither here nor there in the realm of the underworld. Regardless of its value, the fleece can equally serve as a shroud. Macri often incorporates ancient and mythological stories, making them as contemporary as the inventive multi-media artist himself. To the sound of music is added another sound, which at first startles me. Even a ghost may breathe. My breathing is like panting over the keyboard.

The moon is drifting away; I am coming to an end of my confession; the music is about to break my heart. The lovely and emotionally constrained portrait, Memento Mori, brings together many symbolic elements of decay and depletion, a recurring motif in Macri’s art, especially the process of organic rot fomenting new life. Ironically the portrait almost undercuts the import of its title. Reminding us of our human frailty, our mortality, the inevitability of our demise, the portrait is brimming with life. As usual there is the signature combination of the normal with the bizarre; in this instance, seed heads of autumnal flowers and fragments of sloughed off skin, or even pieces of a dead hive covering the skull out of which a tuft of grey hair is seen. From my imaginary position in the wings I am half-tempted to rush on to the stage of this performance and rip it off.

|

| Memento Mori |

Much can be said of the artist’s actual and symbolic handling of hair, although I refrain from doing so here. In this particular series he has often chosen for the most part to pull it back, to shave segments off, for we are going to the bone, as it were, the basic underlying structure. The yellow eyes and the aquamarine stem of stylized, crystalline flowers in front of the bluish-tinged face, the entire portrait overlaid with delicate hues, all elements immeasurably contribute to the visual and vital complexity of this image. I am drawn into its very fibre, the heart of its drama, in order to peruse its ethereal and bodily attributes. I fix my eyes upon the glowing image, the portrait on the monitor framed by the dark of the room. I revel in this sequence of portraits, my self drowning in dissolute desire with the music of Dinu Lipatti playing in the pale reflection of the moonlight. An exquisite pianist, Lipatti died all too young, and so his playing is appropriate for my nighttime ruminations about the celerity of my own dying in Macri’s art.

Resisting temptation to disappear utterly in these silent portrayals, I shall end my confession with a comment on Macri’s complex portrait Icono Emoter because it fits in so well with the theatrical quality of the other faces. It also reminds me that icon, or ikon to use a traditional spelling, is a symbolic image, usually religious in import, a major art form of the eastern Orthodox churches. The images were never meant to be realistic portrayals of human beings, but metaphorical representations of adoration, the sanctity of holiness in the individual saint, and divine connections with the world, so I believe. The icon leads the faithful through the agency of art to an apprehension of God. Macri is, of course, aware of the usage of that word in contemporary culture where it is given instantly and irreligiously to whatever singer or athlete or commercial product or logo catches our collective interest, the antithesis of what the meaning of icon originally signified.

I remember sitting in the gallery devoted to the fabulous icons of Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery. I had gone to see Ilya Repin’s great painting of Ivan the Terrible murdering his son. More by fortuitous accident than deliberate purpose, after wandering about the various rooms, I found my way into this particular display of treasures. After pausing in front of many works of various sizes and intensity, some of the images centuries old, some still brilliant in gold leaf, others faded, I became wearied by what seemed an utterly humorless world of oppressive religion and stiff piety, a painful rigidity, the genius of the art notwithstanding. Behind the complex artistry stands an organized, ritualistic, and highly sensuous faith, which, however meaningful and vibrant for the believer, I myself had abandoned long ago. Breathing difficult because of the sacrosanct atmosphere utterly devoid of eros and the body. To be sure, my response is a purely personal and limited, since the faithful and other lovers of this kind of art experience something else entirely.

Macri’s icon, however, in a sense asks us to create our own meanings. As well constructed as other theatrical and sculptural images, with its brilliantly arrayed components – the elaborate ruff around the neck, for example, and the dragon-like glove or hand puppet (echoes of Vlad Dracul), the loveliness of the lighted skin, the high forehead -- this portrait strikes me as both pagan and satirical. Macri is playing with ideas, which we can interpret as we choose, and he is undercutting our pretensions and perhaps tendency to worship or sacramentalize art, mine among them, just as I suspect he is playing with his own artistry. Sometimes we must laugh at ourselves more than at others. Icono Emoter encourages the viewer to emote, to express one’s feelings, as I am attempting to do as a ghostly presence in the imaginary wings of an imaginary stage. With its props echoing elements in other portraits, and its irreligious manipulation of the ikon, to revert to another spelling, the portrait does not call for belief or worship, certainly not any belief in a codified system of faith, but to enjoy its temerity and playfulness, and perhaps listen long enough to hear the growl of an animal, even a subdued snort of the dragon.

The tragic pianist comes to a rest, perhaps having recorded the last piece before his untimely death. I don’t know. I review all the pictures and notice again the opalescence of several faces almost the same colouring that shifts across the surface of the moon. For a fantastic, ethereal moment, the deathly enchanting image of Mercury of Golden Fleece passes over the glass of the window. His eyes look indirectly into my soul, if soul I have, with invisible fingers strumming my desires, my nerves fibrillating with primordial fantasies. I am excited and saddened. Time is vanishing like the moon. Despite the agelessness of Macri’s portraits, I am no longer young, and for some reason these past nights I have become inordinately conscious of that inescapable fact.

Although the performances have ended, leaving little evidence of my presence backstage, they will resume every time I look at these Macri faces and I see what I didn’t notice before. They change as I change, for Macri’s photographic art, seemingly static, is anything but. Such a subtle, manifold, erotic and vibrant artist of fantasies, multiple identities, and fecund decay. Feeling foolish (Lord, what fools these mortals be, to quote Ariel), I reassemble myself as best I can, depleted and energized despite exhaustion, but remain permanently altered in this world of dissolution and mutations. A kind of anarchy surges through my imagination, which I hesitate to explore. In the middle of the night as I sleep, perhaps those sealed lips in any one of Macri’s stunning portraits will part to release silent words like a poem uttered to the accompaniment of a lyrical pianist in the drama of my chaotic dreams.

Kenneth Radu has published books of fiction, poetry and non-fiction, including The Cost of Living, shortlisted for the Governor General's Award. His collection of stories A Private Performance and his first novel Distant Relations both received the Quebec Writers' Federation Award for best English-language fiction. He is also the author of the novel Flesh and Blood (HarperCollins Canada), Sex in Russia: New & Selected Stories, Earthbound and Net Worth (DC Books Canada).

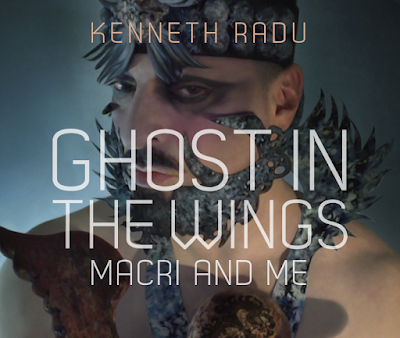

Ghost in the Wings: Macri and Me

Essay by Kenneth Radu - 2015

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

"Over the years as an editor I have discovered that the best writers seldom limit themselves to a single genre. Take, for instance, "Ghost In The Wings" by Kenneth Radu, a creative non-fiction piece in which this short story writer and novelist brings his talents to bear on the topic of art criticism and review. Incredible flexing of substantial literary muscle."

~ Mark McCawley (Canadian fiction writer, poet)

Essay by Kenneth Radu - 2015

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

"Over the years as an editor I have discovered that the best writers seldom limit themselves to a single genre. Take, for instance, "Ghost In The Wings" by Kenneth Radu, a creative non-fiction piece in which this short story writer and novelist brings his talents to bear on the topic of art criticism and review. Incredible flexing of substantial literary muscle."

~ Mark McCawley (Canadian fiction writer, poet)